Resist the Slave Mentality

Compulsory military service in Estonia is a relic of the past, requiring human bodies for war and fostering a slave mentality – a mentality of obedience that sacrifices freedom, equality, and conscience. It is often justified by the need for national security, but compulsory military service ignores countless moral and religious objections, exacerbates gender inequality, and cruelly treats those whose conscience or other beliefs do not allow them to go along with it.

Organizations such as Amnesty International have denounced the practice as a violation of human rights, and the European Court of Human Rights has recognized the right to conscientious objection, but the status quo remains unchanged. In a world that values individual freedoms and equal rights, it is time to let go of the slave mentality. The system must not be blindly accepted but critically evaluated.

HISTORY

Often portrayed as indispensable for national defense, the use of conscription has been influenced by political, economic, and ideological factors. Its implementation in Estonia and neighboring countries reflects historical conflicts and the influence of major regional powers.

Early Origins

In ancient Greece, city-states like Athens and Sparta expected their citizens to participate in the state’s defense, and the Roman Empire used various forms of conscription to build up its vast army.1 These early examples shaped military service as both an obligation and a civil right.2

The widespread use of conscription in the modern era began with the rise of nation-states.3 The first large-scale example dates back to the French Revolutionary War (1790s), when the French Republic, faced with internal and external threats, introduced levée en masse or mass mobilization.4 This policy called for the service of all able-bodied men in the country’s defense, providing a model later adopted by several countries.5

The Russian Empire and Conscription in the Baltic States

Estonia’s experience of conscription began when the country was annexed to the Russian Empire in the early 18th century after the Great Northern War.6 During the reign of Peter I, the Russian army was largely supplemented by compulsory conscription, with peasants and serfs often forced into service for decades.7 This system disproportionately hit the lower classes, while the upper classes could often redeem themselves for freedom.8

For Estonia, the tsarist era of conscription meant not only a burden but also cultural and national oppression. The conscripts were taken away from their families, communities, and mother tongues and placed in Russian-speaking units that served the interests of the empire, not the local population.9 Similar policies were implemented in neighboring Latvia and Lithuania, where local populations often resisted the measures imposed.10

During the First World War, the Russian Empire intensified conscription to fill its gaps, forcing millions of men, including those from the Baltic regions, to the front.11 This period exacerbated resentment of conscription, as the war resulted in huge losses for no perceived benefit to the local population.12

Estonian Independence and the Interwar Period

After World War I and the collapse of the Russian Empire, Estonia declared independence in 1918. 13 During the War of Independence (1918–1920), volunteer forces played a key role, successfully helping to repel both the Bolshevik and German threats. Although the young Republic of Estonia introduced compulsory military service, it was seen more as a temporary emergency for the state’s survival than an indisputable obligation.14

Although the young Republic of Estonia introduced compulsory military service, it was seen more as a temporary emergency for the state’s survival than an indisputable obligation.

During inter-war, Estonia maintained compulsory conscription to ensure its national defense. Neighboring countries such as Latvia, Lithuania, and Finland did the same, relying on citizen armies to deter larger aggressors. At the same time, the experience of the First World War and the heavy burden of conscription in rural areas fostered a reluctance to compulsory conscription. 15

Soviet Occupation and Forced Conscription

For Estonia, conscription became most oppressive during the Soviet occupation during and after World War II.16 After the annexation of Estonia in 1940, the Soviet Union began to implement compulsory military service, forcing young Estonian men into the Red Army. Many were sent to violent and brutal conditions far from home, where they were treated suspiciously as the population of occupied territories. 17

During the German occupation (1941-1944), the Nazis also introduced forced military service, recruiting Estonians into the auxiliary forces and the Waffen-SS.18 This left many Estonians caught between two oppressive regimes, forced to fight in the interests of foreign powers.19

After the Second World War, the Soviets reintroduced conscription, which became a symbol of both national oppression and Russification. Estonian men were sent to distant Soviet regions, where their national identity was ignored and their culture stifled. 20

Modern Day

After Estonia regained its independence in 1991, conscription was restored as part of national defense.21 Nowadays, conscription is compulsory for men aged 18-27, justified by the need to have trained reserve forces.22

Although conscription has been part of the history of Estonia and neighboring countries, the system originates from outdated warfare and state control models. From Tsarist coercion to Soviet repression, compulsory military service has often been a source of resistance and discontent. In today’s world, where individual freedom and human rights are valued, the continuation of conscription raises serious moral, ethical, and practical questions. Accepting the status quo is not enough: the origins and consequences of conscription need to be critically analyzed to find better solutions that respect national security and personal autonomy.

MORALS AND ETHICS

Compulsory military service raises serious moral and ethical questions that question its legitimacy in a modern democratic society. While proponents argue that conscription ensures national security and fosters civic responsibility, its implementation often violates fundamental human rights, perpetuates inequality, and ignores individual autonomy.

Personal Freedom and Autonomy

Military service imposes a state obligation that puts the needs of the state above personal freedoms, forcing people to relinquish control of their lives for a set period. Such coercion is contrary to international human rights instruments such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which guarantees the right to liberty and security of person (Article 3) and freedom of thought and conscience (Article 18). 23

In Estonia, men aged 18–27 are required to complete mandatory military service, with penalties such as fines and the suspension of various rights and licenses imposed for refusal.24 This system restricts young men from choosing their career path, continuing their education, or making significant life decisions.

Religious and Moral Beliefs

Military service often conflicts with the religious and moral convictions of people who refuse to serve. Conscientious objectors face serious obstacles, including social stigma and limited alternatives in Estonia. These problems persist despite international standards, as defined by the European Court of Human Rights, which has upheld the right to freedom of conscience in cases such as Bayatyan v. Armenia (2011).25

Religious groups such as Jehovah’s Witnesses and pacifists often cite their beliefs as grounds for refusing to serve.26 However, the punitive measures imposed on these individuals by many countries show that religious freedom and personal conscience are not sufficiently respected.27 What is more, these principles are explicitly protected by Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights.28

Psychology

Compulsory military service interrupts lives, careers, and education, with long-lasting social and psychological effects, as young people are often called up at a formative stage in their lives, delaying or hindering personal and professional development. In Estonia, many conscripts express dissatisfaction with the interruption of their education or the postponement of starting a career while at the same time referring to the psychological stress of the strict military environment of conscription. 29

Studies have linked compulsory military service to increased mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Participants in military service have higher levels of psychological distress, many times more anxiety disorders, and so on. 30

Sacrificing Life and Taking an Oath

Military service requires people to be prepared to kill or die for their country, raising serious moral dilemmas. While some argue that it is justified in the name of defending the state, others believe that forcing someone to risk their life violates their fundamental right to self-determination. 31

In addition, the forced swearing of an oath of allegiance is problematic. In the Estonian Defence Forces, every person entering military service must sign the following oath:32

“I, (name and surname), swear to remain loyal to the democratic Republic of Estonia and its constitutional order, to defend the Republic of Estonia against the enemy with all my wits and strength, to be ready to sacrifice my life for the fatherland, to observe the discipline of the Defence Forces, and to perform all my duties accurately and unquestioningly, bearing in mind that otherwise I will be severely punished by law.”.

Such a declaration requires young people to make forced life-and-death decisions in a situation where they have no free choice. A pledge that presupposes a willingness to sacrifice life and obey without hesitation is contrary to the principles of conscience and self-determination. Moreover, such an order positions the agencies beyond critique, creating a risk of unchecked authority and potential abuses. 33

INEQUALITY

Compulsory military service is one of the last “legal” systems that openly discriminate against people based on gender, placing a disproportionate demand on men.34 The continuation of this system not only perpetuates outdated gender roles but also reflects deep structural inequalities, where men’s bodies are seen as belonging to the state, while women have no such obligation.

Unequal Impact on Men

Only men in Estonia are subject to compulsory military service, while women may volunteer.35 This creates a clear double standard, where men are seen as “tools of the war machine”, while women are exempted from the state’s obligation to participate in direct national defense. In addition to gender equality (advocated by the European Union36), it also reinforces outdated perceptions of the roles of men and women in society.

The current military service organization assumes men have no autonomy over their bodies and lives. At the same time, it puts their physical and mental health at risk by taking men for granted as victims to be exploited in the name of national interests. 37

The ethical problem with this approach is that men’s bodies are seen as a resource that can be used and sacrificed by the state. This presumption diminishes the individual’s freedom and worth, reducing men to mere means to achieve state ends. The paradigm of forced conscription fosters an authoritarian mindset that is inappropriate for a democratic society based on human rights.

The slave mentality paradigm fosters an authoritarian mindset that is completely incompatible with a democratic and human rights-based society.

Reinforcing Structural Inequalities and Gender Roles

The military service system reinforces that men’s value lies in their physical strength and willingness to fight, while women’s value is seen more in civilian and family roles. Such gender roles are deeply rooted in historical perceptions, but in modern society, such expectations are outdated. 38

Although some countries (such as Norway and Sweden) have introduced gender-neutral conscription, this approach is not achieved in Estonia and most other countries.39 At the same time, the voices of men who wish to opt out of the system are ignored and often stigmatized or punished.40

Gender Identity

In today’s legal and social context, where gender self-determination is increasingly recognized as a human right, the system of conscription is outdated. Recognition of gender identity allows individuals to define their gender identity according to how they see themselves, supported by several international agreements and national laws. 41

In Estonia, gender self-determination is currently very limited, and the process of gender reassignment can take years, so there is no flexibility in the context of military service obligations, and the entire process is much more complicated than elsewhere. 42 This ignores the individual’s right to self-determination and contemporary understandings of gender diversity.

Malta43 and Norway44 have already integrated gender self-determination protection mechanisms into their legislation to ensure that national systems do not discriminate against people based on their identity. However, Estonia continues to ignore the fact that such rigidities impose an additional burden on transgender people and ignore their rights.

HUMAN RIGHTS

Compulsory military service in Estonia contradicts internationally recognized human rights principles, at the core of which are personal autonomy, dignity, and the right to make ethical choices. This practice cannot be considered a mere measure of national security if its implementation violates fundamental rights such as freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. International treaties and decisions, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), set clear standards that compulsory military service in Estonia violates.

Freedom of Thought, Conscience, and Faith

Article 18 (UDHR) guarantees everyone the right to follow their conscience, including the freedom to change their religious and philosophical beliefs. 45Military service violates this right by forcing people to engage in activities that may conflict with their ethical and religious beliefs.

Penalties and social stigma for refusal are in clear violation of Article 18 of the UDHR, which requires states to respect freedom of religion or belief and freedom of conscience.46

Article 18 of the ICCPR extends the principles of Article 18 of the UDHR by stressing that no one shall be compelled to commit acts contrary to his conscience.47 The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has confirmed in cases such as Bayatyan v. Armenia that compulsory military service without effective alternatives violates human rights.48

Ban on Forced Labour

Article 8 of the ICCPR prohibits forced labor except in certain limited cases, such as imprisonment as a punishment.49 Compulsory military service, especially in situations where alternatives are not offered, are not sufficiently available, or are discriminated against, qualifies as forced labor.

In Estonia and in many other countries, young men have to do military service, which often involves physically and mentally demanding conditions.50 When individuals are forced to give up their rights and freedoms as a result of state coercion, this contravenes the international prohibition of forced labor and respect for human dignity.

Equality Before the Law and Non-Discrimination

Article 26 of the ICCPR guarantees that all persons are equal before the law and must be protected against discrimination, including discrimination based on sex, religion, or other status.51 Compulsory military service, however, reinforces structural inequalities and perpetuates outdated gender norms by targeting only men. Compulsory conscription based on gender does not comply with Article 26 of the ICCPR, which requires all laws and policies to respect the principle of equality.52

Gender-based compulsory military service is not in line with Article 26 of the ICCPR, which requires that all laws and policies respect the principle of equality

Amnesty International’s Position

Amnesty International, the international human rights organization, has repeatedly stressed that forcing someone to participate in military activities or military training if it is against their conscience or religious beliefs is a fundamental violation of human rights.53

Amnesty’s position upholds the principles of international treaties and resolutions, requiring states to provide alternatives to conscription and respect individuals’ right to refuse to participate in military structures.

PRACTICAL PROBLEMS

Compulsory military service, once a necessary solution to ensure the security of nation-states, has lost its effectiveness and relevance in the context of the 21st century. The system’s shortcomings are evident in terms of cost-effectiveness, military effectiveness, and motivation. 54

Inefficiency and Cost

Compulsory military service is extremely expensive. Training, equipping, and integrating young people into the temporary military system requires considerable resources, but their military contribution is often limited. In Estonia, the Defence Forces have been concerned about the health and preparedness of conscripts: the 2023 report highlighted an increase in mental health problems among conscripts, including panic disorders and depression.55 Such problems reduce their ability to serve effectively while increasing costs.

In comparison, Sweden and Norway have restricted conscription and focused more on volunteering and a professional army.56 Sweden, which partially reinstated conscription after 2017, selects only a small percentage of the most suitable candidates.57 This approach ensures that resources are used more efficiently, and the focus is on motivated soldiers.

Lack of Motivation

Motivation is not forced. Compulsory military service often produces demotivated and reluctant soldiers. Young people who do not feel a vocation or interest in military service may be unwilling to perform their duties, reducing the morale and effectiveness of the force. 58

Germany abolished compulsory conscription in 2011 and found the volunteer army more motivated and effective. 59

Germany abolished compulsory military service in 2011 and has found that the volunteer army is more motivated and effective.

Modern Day

21st-century warfare requires highly trained professionals and sophisticated technological systems, not enormous human resources.60 Short-term manpower acquired through compulsory military service cannot meet the requirements of today’s battlefields, which include cyber defense, drone technology, and high-tech intelligence.61 By comparison, the UK, which has retained a fully volunteer armed forces, has been able to focus on technological innovation and globalised security needs without compulsory service.62

As a member of NATO, Estonia has changed its approach to defense needs, focusing more on collective defense and international cooperation. NATO membership provides Estonia with a strong safety net, with an emphasis on common Alliance resources and professional cooperation.63 Meeting NATO standards also means the deployment of higher quality personnel and technology, which is rarely met by forced conscripts.64

Success Stories From Europe

Several European countries have abandoned compulsory military service and have shown significant progress. For example:

– Germany abolished compulsory military service in 2011, citing its cost and inefficiency. Instead, the country focuses on a professional and voluntary defense system. 65

– The Netherlands abandoned compulsory conscription in 1997, moving to an all-volunteer army. Since then, the Netherlands has invested in high-tech solutions and international cooperation. 66

– Sweden has limited the scope of conscription and focuses on highly motivated candidates, thus ensuring better use of resources and higher levels of preparedness.67

BETTER PLAN

Compulsory military service in Estonia has lost its moral and practical justification, especially given modern alternatives that guarantee national security and respect for individual rights. Many countries have successfully moved towards professional volunteer armies that attract motivated and skilled personnel without coercion. There is, therefore, no need to invent the bicycle.

Volunteer Army

One of the main alternatives to conscription is the professional voluntary army, which several European countries offer. One of the best examples is the Netherlands, which abandoned compulsory conscription in 1997, shifting resources to a professional army and NATO international cooperation. The result is a more effective and motivated defense force. 68

Estonia could implement a broad volunteer reserve force program, where citizens participate in voluntary exercises and can support a professional army in crises. Finland and Sweden are examples of countries where reserve forces are strongly developed. Sweden selects only motivated candidates for military service and then offers the possibility to join the reserve forces.

Many skeptics might argue that a volunteer army is costly. However, the Estonian Ministry of Defence’s 2024 budget shows that significant investment is already being directed toward modern defense equipment and technologies. The budget totals €1.02 billion, of which €338 million is earmarked for the Defence Forces, €628 million for the Defense Resources Agency and €572 million for management costs.69 With these amounts, an efficient and professional recruitment program can be implemented, reducing the costs of managing forced conscription.

Creating a volunteer army in Estonia is not only possible, but there are favorable conditions for it.

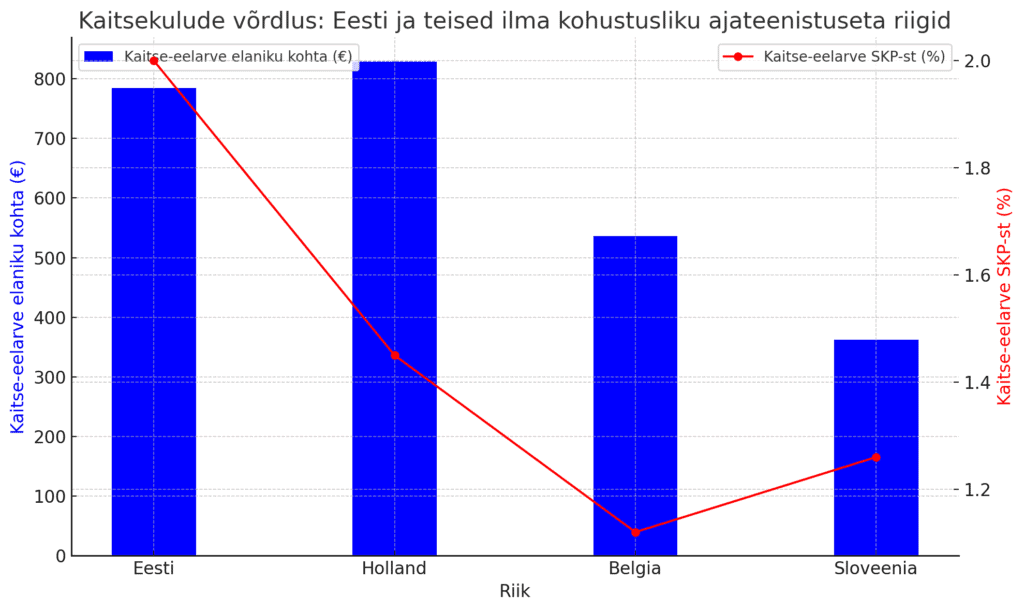

Comparing Estonia with other EU member states that do not have forced conscription, it is obvious that Estonia not only has the potential to create a volunteer army but also has favorable conditions for it:

HEROES

Throughout history, people have resisted slavery and compulsory military service, opposing systems that demand unquestioning obedience at the cost of personal freedoms, ethics, and beliefs. These heroes have paved the way for wider debates on the morality of conscription and inspired movements for greater recognition of human rights.

Osman Murat Ülke (Turkey)

Osman Murat Ülke spectacularly burned his draft card in 1995 – an act of courage that led to repeated arrests, imprisonment, and harassment for more than a decade.70 Despite inhumane conditions and societal pressures, Ülke stood by his convictions, claiming that conscription violated his autonomy and pacifist beliefs.71

In 2006, the European Court of Human Rights ruled in favor of Ülke, noting that Turkey’s treatment of him constituted inhuman and degrading treatment, in violation of Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights.72 This established a precedent for conscientious objectors both in Turkey and beyond.

Muhammad Ali (United States)

Legendary boxer Muhammad Ali attracted widespread attention in 1967 when he refused to join the US military during the Vietnam War, citing his religious beliefs in Islam and anti-war views.73 His refusal led to the revocation of his boxing titles and a conviction for evading service.74

In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Ali’s conviction, recognizing his refusal on religious grounds. 75

Franz Jägerstätter (Austria)

Austrian peasant and Catholic Franz Jägerstätter refused to fight for Nazi Germany during the Second World War.76 Citing his opposition to the regime’s immoral war, he persevered despite pressure from the community and the Church.77 In 1943, Jägerstätter was executed for his refusal, making him a martyr for refuseniks around the world. 78

In 2007, Pope Benedict XVI issued an apostolic exhortation, acknowledging his moral courage and sacrifice as an example of unwavering ethical resistance. 79

End Conscription Campaign (South Africa)

The End Conscription Campaign (ECC), created in the 1980s, sparked widespread resistance among young white men who refused to serve in an unfair system.80 The ECC’s activism helped undermine support for apartheid and highlighted the role of conscientious objection in social change.81

Jehovah’s Witnesses: South Korea and Russia

Jehovah’s Witnesses have long been at the forefront of the fight against conscription, as their faith forbids military service.82 Thousands of Jehovah’s Witnesses were imprisoned in South Korea every year until 2018 for refusing military service.83 One of the most notable victories came in 2018 when South Korea’s Constitutional Court ruled that freedom of conscience should be recognized as a valid ground for conscientious objection.84 Since then, thousands of Jehovah’s Witnesses have been released from prison or acquitted of charges, demonstrating the power of persistent resistance and legal defense.85

In Russia, Jehovah’s Witnesses continue to face persecution.86 Despite the risks of imprisonment and social exclusion, many are determined to remain true to their beliefs.87 The international community, including organisations such as Amnesty International, has repeatedly called for the protection of their rights, stressing the need to oppose such systems.88

Zwaan-de Vries (Netherlands)

Although this case was not directly related to conscription, it concerned an important issue of discrimination: Zwaan-de Vries is a Dutch woman who was refused unemployment benefits on the grounds of her gender.89 The UN Human Rights Committee found that the Netherlands had violated Article 26, the principle of equality before the law and non-discrimination.90

The Vries case illustrates how legislative restrictions that discriminate against people based on gender, religion, or moral beliefs can violate internationally recognized human rights. The same logic applies in the context of military service.

André Glor (Switzerland)

André Glor refused conscription on health grounds and offered alternative civilian service instead, but Swiss law did not recognize his offer as he was not formally exempt.91 The ECHR found that Switzerland had violated his right not to be discriminated against (Article 14), together with the right to respect for private life (Article 8).92

Eritreans Fleeing Conscription

In Eritrea, compulsory military service is of indefinite duration, often comparable to modern slavery, where young people are forced to live for years in military camps without the freedom to decide about their lives.93 The UN International Commission of Inquiry has repeatedly stressed that such a system violates human dignity and contravenes international standards, including the prohibition of forced labor.94

Thousands of Eritreans flee their homeland every year, risking their lives to escape across deserts and waterways.95

Guy Davidi (Israel)

In Israel, a documentary film, Innocence, was produced in 2022, which talks about the impact of military propaganda culture on young people, focusing on the example of Israel. 96 The film reveals how young people are drawn into military service using promises and manipulation, with the story centered on children who initially resisted conscription but eventually succumbed to pressure. 97 Their lives, internal conflicts, and tragic fates are revealed through diaries, military videos, and home recordings, showing how their deaths have been silenced and portrayed as a threat to the national narrative. 98 The film invites discussion on the issues of militarism and moral corruption. 99

S. Landau, I. Saraf, R.O. Moore (United States)

The documentary From Protest to Resistance (1968) explores the movement against conscription and the Vietnam War in the United States.100 It shows how young men and women took up protests against an unjust war and conscription that forced them to participate in a conflict with which they morally disagreed.101 The film looks at the evolution of the movement from peaceful protest to outright resistance, including refusal to participate and imprisonment.102 Using archival footage and activists’ stories, the documentary shows how compulsory conscription became a central issue and symbol of the anti-war movement’s struggle to defend individual rights and conscience.103 The film confirms that collective resistance can bring change, even in seemingly immutable systems.

COMMON MYTHS

Common myths about compulsory military service are deeply rooted but do not stand up to critical reflection. Patriotism does not require forced labor, equality cannot be achieved through systemic discrimination, and 21st-century defense requires professionalism and will, not coercion, not to say slavery. Instead of clinging to the dustbin of history with ten nails, states should embrace modern, ethical, and voluntary alternatives that respect human rights and guarantee collective security.

“Participation in military service is patriotic and every man’s duty”

One of the most common myths is that military service is a patriotic and moral duty for every man.104 In reality, patriotism does not require blind obedience to authority or participation in militarism; true patriotism consists of critical thinking and pursuing a society that promotes justice, equality, and individual freedoms.105 Forcing people into service that denies their right to choose undermines democratic values and individual freedoms.106 Countries such as Germany have abolished compulsory conscription but maintained a high level of national pride and an effective military.107

“Military service boosts equality and cohesion”

The systems of military service are often steeped in inequality. Wealthier people or those with connections often have the opportunity to evade service, while the burden falls disproportionately on marginalized and less privileged groups.108 The current system of compulsory military service for men only in Estonia exacerbates gender discrimination and perpetuates outdated gender roles.109 Moreover, compulsory service does not create real cohesion but often creates resentment and divisions between those forced to serve and those exempt.110 Voluntary service programs are much more effective in creating real social cohesion.111

“There is alternative service”

Alternative service is offered as an alternative to conscription, but its availability is limited, and in practice, it serves only as a form of forced labor. Many applicants are denied access to alternative services due to limited places and still have to undergo military training or face penalties.112 At the same time, the Defence Resources Agency requires a motivated request and precise explanations of religious and other reasons.113 – this is contrary to the principle of freedom of religion, and no one can be obliged to disclose such personal information, which may result in the rejection of the request.114. In addition, posts in the alternative service often involve tasks unrelated to national defense and do not substantially benefit society.115 At the same time, they are low-paid, which makes the system unequal and inherently extortionate. Replacement service does not solve the fundamental problem of compulsory service, which remains an imposition imposed by the state that restricts individual freedom and rights. If such tasks are necessary, they could be carried out by volunteers or real paid workers.

“Military service is indispensable for national defense”

Some believe that conscription in Estonia is essential for national security, especially in smaller countries facing potential threats. Modern warfare relies more on technology, specialization, and professionalism than on large numbers of minimally trained conscripts.116 As a NATO member state, Estonia has a collective security system that reduces the need for mass conscription.117 Sweden and Norway have moved towards limited or selective conscription and professional armies, showing that a strong defense capability does not require compulsory service for all.118 Modern warfare requires motivated and highly trained professionals, not temporary forced labor resources.119

“Warfare is not for women”

The argument that women are not fit for the defense forces or should not be obliged to do military service is based on outdated and sexist gender stereotypes.120 Ability is not a gender-based, but an individual characteristic, and excluding women from the compulsory system is instead unjustified discrimination.121 History and experience have repeatedly proven that women can perform military tasks just as successfully as men.122 Many women have already proven their skills in demanding roles, both in leadership positions and on the battlefield.123 The exclusion of women from military service dates back to the same era when women did not have the right to vote; which has been changed, but military service has not.124

“The easiest way to pass conscript services is to just do it”

Many people mistakenly believe that their ties with the Defence Forces end after completing their military service. Still, in reality, both those who have completed their military service and those who have been released for various reasons are counted as reserves, meaning that their commitment to the state continues indefinitely.125 Reservists must be aware that they may be called up for training or mobilization at any time and that their presence is also a legal obligation.126 These gatherings may disrupt an individual’s professional and private life, creating an additional burden not initially foreseen. The system creates a situation in which the individual is tied to the state throughout his or her life and must essentially sell out to the state.

“Military service is safe and attended by healthy conscripts”

Safety may indeed have improved over the years, but incidents still happen, and an environment where firearms, explosives, and military equipment are used cannot be safe. 127 Some examples:

– 1997, 14 soldiers drowned or died of hypothermia in Estonia128

– In 2010, a conscript in Estonia was seriously injured during an exercise, and another conscript was caught between two vehicles129

– In 2012, an alleged incident occurred in Estonia where conscripts were forced at gunpoint to dig their own graves130

– In 2018, a 19-year-old was seriously injured in a grenade explosion in Estonia131, and a conscript died due to breathing difficulties that began during service132

– In 2019, a conscript in Russia killed 8 fellow conscripts due to humiliation133

– In 2021, a conscript in Estonia died as a result of a firearm injury134

– In 2022, a conscript died in a field camp in Estonia135

– In 2024, a Polish military aircraft pilot died during a training flight136, and in Finland, 23 conscripts were seriously injured during a shooting exercise137

In recent years, health requirements have been relaxed to increase the number of eligible conscripts. 138 As a result, people with chronic illnesses, including those diagnosed with diabetes, cancer, asthma and behavioural disorders, are also being called up for service. 139 Forcing young people with illnesses into military service can be particularly dangerous and violate the principles of human dignity, as they are forced to participate in physically and mentally exhausting activities that can further deteriorate their health. 140 Young people who are called up for military service with chronic illnesses or mental health problems often face situations where there is a lack of adequate medical support or consideration for their special needs. 141

LET’S CHOOSE FREEDOM

It is time to ask whether we need a system that undermines human dignity and democratic values.

Military service is not just a state obligation but a method of coercion that requires obedience and silences critical thinking. It creates a slavish mentality where the individual is not allowed to ask “why?” but must obey orders without question. Such an approach is incompatible with the ideals of a modern, educated, and free society where every individual’s voice and choice should matter.

Modern warfare no longer needs a mass workforce but highly skilled and motivated specialists. As a NATO member state, Estonia can rely on cooperation between allied forces and invest in new solutions. As such, conscription in Estonia is outdated and more characteristic of the Soviet Union than the Republic of Estonia.

Forced conscription as such is outdated and characterizes the Soviet Union more than the Republic of Estonia.

It is essential to respect the right of every individual to autonomy and conscience. Cases of conscientious objection to military service in Estonia and internationally show that forced service does not align with modern values. Cases of conscientious objection prove that a person can be stronger than the system that tries to subjugate him.

Abolishing conscription would be a step forward in strengthening democracy and respecting individual rights. It does not mean abandoning the defence capability, but rather bringing it to a level that is efficient, professional and in line with human rights.

Continuing forced conscription does not support Estonia’s future. Instead, we must choose a path that respects national security and every individual’s dignity and autonomy. Freedom does not come from slavery. We choose freedom.

Sources

- The Shire. Bred for Battle—Understanding Ancient Sparta’s Military Machine ↩︎

- Legacy of Greece and Rome. Civic duty ↩︎

- E. Storm. The rise of the nation-state during the age of revolution: revisiting the debate on the roots of nations and nationalism ↩︎

- H. Mark. French Revolutionary Wars ↩︎

- A. Caiani. Mass uprising ↩︎

- A. Janicki. Russian Expansion in the Baltic in the 18th Century ↩︎

- Wikipedia. Serfdom ↩︎

- R. Bartlett. Serfdom and State Power in Imperial Russia ↩︎

- K. Piirimäe. From an ‘Army of Historians’ to an ‘Army of Professionals’: History and the Strategic Culture in Estonia ↩︎

- A. Petrauskaite. Nonviolent civil resistance against military force: The experience of Lithuania in 1991 ↩︎

- National Archives. Soldier and the law ↩︎

- K. Richter. Baltic States and Finland ↩︎

- Estonian Encyclopedia. The birth of Estonian independence (1917–1920) ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Wikipedia. Estonia in the First World War ↩︎

- K. Luts. Estonian conscripts in the Soviet Union armed forces during the Cold War ↩︎

- Wikipedia. Soviet occupation of Estonia (1940–1941) ↩︎

- P. Kaasik. Eesti rahvaväe moodustamise kava 1943. aastal ↩︎

- P. Shadow. Estonian men in World War II ↩︎

- Communist crimes. Estonia ↩︎

- A. Laaneots. Restoring Estonian national defense – the first steps ↩︎

- Wikipedia. Conscription ↩︎

- United Nations General Assembly. Universal Declaration of Human Rights ↩︎

- State Gazette. Section 331 of the Civil Code ↩︎

- European Court of Human Rights. Bayatyan v. Armenia ↩︎

- Official website of Jehovah’s Witnesses. Why don’t Jehovah’s Witnesses join the military? ↩︎

- D. Cai. The men going to military jail for their faith ↩︎

- State Gazette. Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms ↩︎

- E. Demus. Satisfaction with conscription and factors influencing it in the Estonian Defence Forces ↩︎

- U. Wesemann, K. Renner et al. Incidence of mental disorders in soldiers deployed to Afghanistan who have or have not experienced a life-threatening military incident—a quasi-experimental cohort study ↩︎

- E. Arnet. The ethics of conscription ↩︎

- State Gazette. Section 10 of the Civil Code ↩︎

- J. Montrose. Unjust war and a soldier’s moral dilemma ↩︎

- S. Stakhovich and S. Strand. Preserving and progressing: tensions in the gendered politics of military conscription ↩︎

- Defence Resources Agency. Women and conscription ↩︎

- European Commission. Gender equality ↩︎

- D. Bethmann and J. Cho. Conscription hurts: the effects of military service on physical health, drinking, and smoking ↩︎

- M. Gibbons. Military conscription, sexist attitudes, and intimate partner violence ↩︎

- Š. Šťastníková. Rethinking conscription: the Scandinavian model ↩︎

- Amnesty International. South Korea: drop charges against first conscientious objector to refuse alternative service ↩︎

- Silga. United Nations: 28 states call for legal gender recognition based on self-identification ↩︎

- M. Hindre. New regulation could make gender reassignment easier ↩︎

- LGBTI equality and human rights in Europe and Central Asia. Malta celebrates landmark gender identity law ↩︎

- Amnesty International. Norway: historic breakthrough for transgender rights ↩︎

- United Nations General Assembly. Universal Declaration of Human Rights ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- State Gazette. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ↩︎

- European Court of Human Rights. Bayatyan v. Armenia ↩︎

- State Gazette. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ↩︎

- FitQ. Estonian youth and their willingness to serve in the Defence Forces ↩︎

- State Gazette. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- War Resisters’ International. Amnesty International public statement on conscientious objection ↩︎

- P. P. Poutvaara and A. Wagener. Conscription: economic costs and political allure ↩︎

- ERR. Mental health problems are increasingly prevalent among those called up for military service. ↩︎

- P. Szymański. Universal, selective, and lottery-based: conscription in the Nordic and Baltic states ↩︎

- ERR. Swedish Defence Force Chief: Reinstating conscription will strengthen the army ↩︎

- E. Jonsson, M. Salo, E. Lillemäe et al. Multifaceted conscription: a comparative study of six European countries ↩︎

- M. Bacolod and S. Koenigsmark. When Germany ended conscription, and an era: effects on composition and quality of its military ↩︎

- M. Channan. Beyond the battlefield: the skills and strategies needed for 21st-century military leadership ↩︎

- S. Lingel. Identifying future technology and workforce requirements for air operations: the strategies-to-tasks approach ↩︎

- Wikipedia. Volunteer reserves (United Kingdom) ↩︎

- Ministry of Defence. NATO collective defense ↩︎

- S. Wilcock. Managing quality in defense ↩︎

- Wikipedia. Conscription in Germany ↩︎

- C. Klep. Peacekeepers in a warlike situation: the Dutch experience ↩︎

- Delphi. Rootsi muutis armee noortele huvipakkuvaks. Ajateenistuse taastamist tuuakse teistele eeskujuks ↩︎

- Dutch Ministry of Defence. Military contribution to NATO in 2024 ↩︎

- Ministry of Finance. 2024 state budget ↩︎

- War Resisters’ International. The case of conscientious objector Osman Murat Ülke ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- European Court of Human Rights. Country v. Turkey ↩︎

- D. Zirin. When Muhammad Ali Took the Weight ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- M. Wills. How Muhammad Ali prevailed as a conscientious objector ↩︎

- The National WWII Museum. The Story of Austrian Catholic Resister Franz Jägerstätter ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- W. Jabusch. Franz Jägerstätter: The Austrian farmer who said no to Hitler ↩︎

- South African History Online. End Conscription Campaign (ECC) ↩︎

- Wikipedia. End Conscription Campaign ↩︎

- Official website of Jehovah’s Witnesses. Why don’t Jehovah’s Witnesses join the military? ↩︎

- Official website of Jehovah’s Witnesses. Historical events in South Korea ↩︎

- The New York Times. In landmark ruling, South Korea’s top court acquits conscientious objector ↩︎

- Official website of Jehovah’s Witnesses. All witnesses imprisoned for conscientious objection in South Korea now free ↩︎

- Religion News Service. 9 Jehovah’s witnesses convicted of extremism for practicing faith in Russia ↩︎

- M. Parts. What is happening to Jehovah’s Witnesses is paving the way for wider persecution ↩︎

- Amnesty International. Early release of Jehovah’s witness reverted ↩︎

- International Network for Economic, Social & Cultural Rights. FH Zwaan-de Vries v. the Netherlands, Communication No. 182/1984 (9 April 1987), UN Doc. Soup. Well. 40 (A/42/40) at 160 (1987) ↩︎

- Legal Information Institute. Zwaan-de Vries v. The Netherlands ↩︎

- European Court of Human Rights. Glor v. Switzerland ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Human Rights Watch. “They are making us into slaves, not educating us” ↩︎

- UN. UN Inquiry finds crimes against humanity in Eritrea ↩︎

- M. Belloni. Young Eritreans explain why they are fleeing the country ↩︎

- IMDB. Innocence ↩︎

- Cinema Politica. Innocence ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- R. S. Ross. Innocence: a furious documentary suffused with grief ↩︎

- WNET. Full film & more: from protest to resistance (1968) ↩︎

- American Archive of Public Broadcasting. NET Journal; 189; from protest to resistance ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- U. Meinhof. From protest to resistance (1968) ↩︎

- C. Ryan. Democratic duty and the moral dilemmas of soldiers ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Britannica. Mandatory national service ↩︎

- Wikipedia. Conscription in Germany ↩︎

- A. Asoni, T. Sanandaji. Rich man’s war, poor man’s fight? Socioeconomic representativeness in the modern military ↩︎

- State Gazette. Section 2 of the Civil Code ↩︎

- V. Bove, R. D. Leo, M. Giani. What do we know about the effects of military conscription? ↩︎

- A. Gillette. Voluntary service and social cohesion ↩︎

- Ministry of Defence. Aruanne kaitseväekohustuse täitmisest ja kaitseväeteenistuse korraldamisest 2023. aastal ↩︎

- Defence Resources Agency. Substitute service ↩︎

- Equality and Human Rights Commission. Religion or belief: is the law working? ↩︎

- Defence Resources Agency. Substitute service ↩︎

- S. Strand. The “Scandinavian model” of military conscription: a formula for democratic defense forces in 21st century Europe? ↩︎

- Ministry of Defence. NATO collective defense ↩︎

- J. Buchar. The inspirational Swedish model of military service: seven percent of the most capable recruited annually ↩︎

- G. Barndollar. Sweden’s new model army ↩︎

- K. French. We are all green: stereotypes for female soldiers and veterans ↩︎

- L. Jäncke. Sex/gender differences in cognition, neurophysiology, and neuroanatomy ↩︎

- D. Gresik. 8 female soldiers who changed the course of US military history ↩︎

- USO. 15 women making modern military history ↩︎

- E. Allen. World War I: conscription laws ↩︎

- State Gazette. Section 70 of the Civil Code ↩︎

- Defence Resources Agency. Reserve service ↩︎

- UK Ministry of Defence. Safety and environmental management of ordnance, munitions and explosives over the equipment acquisition cycle ↩︎

- Postimees. TODAY IN HISTORY ⟩ 14 Estonian soldiers died in the Kurkse tragedy ↩︎

- Evening newspaper. Helmet saved the life of a soldier who was hit head-on by a howitzer ↩︎

- ERR. Newspaper: Two conscripts forced to dig their own graves at gunpoint ↩︎

- ERR. “Eyewitness”: Grenade accident in the Defence Forces could have ended much worse ↩︎

- ERR. Health problem claimed the life of a conscript ↩︎

- Postimees. Conscript who killed eight soldiers in Russia: I couldn’t take the humiliation anymore ↩︎

- Southern Estonian. A conscript died at the logistics battalion field camp. ↩︎

- Estonian Defence Forces. A conscript died at the Kuperjanov Infantry Battalion field camp. ↩︎

- T. Ozturk. Polish military plane crashes during airshow rehearsals, killing pilot ↩︎

- MTV News. 23 conscripts in accident in Ivalo – tracked truck overturned during shooting exercise ↩︎

- Postimees. List: Those with these health problems will no longer be able to escape military service ↩︎

- State Gazette. Health requirements for persons subject to military service ↩︎

- B. Mieziene, A. Emeljanovas et al. Health behaviors and psychological distress among conscripts of the Lithuanian military service: a nationally representative cross-sectional study ↩︎

- H. Frilander, T. Lallukka et al. Health problems during compulsory military service predict disability retirement: a register-based study on secular trends during 40 years of follow-up ↩︎